Is VR really a good way of teaching children SEL? VR has been around for longer than most people realize, with its first forms emerging in the 1980s. However, it did not become widely accessible until around the 2000s. With greater accessibility comes greater power. Just like with other forms of technology, VR can be used for many purposes—including teaching youth about the important skills needed to lead healthy social lives with themselves and others. Resilience Inc. is a company that is taking VR to new heights in its uses. As part of Resilience Inc.’s curriculum, students can immerse themselves in an interstellar world where they learn the skills and exercises needed to help regulate anxious feelings. The questions then emerge: how does VR teach us these beneficial skills and how efficient is VR at education?

VR in SEL programs usually take the forms of either virtual worlds, games, or simulations. In each of these forms, VR provides an immersive environment that brings out genuine emotions and reactions. People tend to see their virtual experiences as really happening to them at the moment. This effect on players is increased when the characters in the VR experience are human actors and when these characters make eye contact with the player (camera placement for VR matters!) The positive and negative emotions that are evoked by VR can be used to increase learning. For example, negative emotions can help the player focus attention on the mission at hand.

Another way VR can uniquely help us learn important skills is it provides players with a safe environment for them to learn and practice new skills without serious consequences. Through their interactions with the virtual world, they may be able to grasp different social contexts that they can then apply to the real world. Since these experiences are virtual, players can repeat the lessons as many times as needed to truly understand the concepts being taught through these programs.

Generally, VR seems to be very effective at teaching skills, especially for students who have certain mental disabilities. Those with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) are one such group of kids that can benefit from being taught social skills and self-regulation skills through VR. Generally, those with ASD tend to react better to electronic means rather than human interaction; VR plays to these preferences, providing support in their social development. This is supported by an observed increase in social and emotional competencies in those with ASD after participating in a VR SEL curriculum over various studies. Furthermore, when combined with reflection, VR is even more effective at teaching people skills, requiring people to make sense of their experience and engage with the concepts they’ve learned. Overall, VR seems to be a good mode for teaching SEL to children.

Check out Resilience Inc.’s VR game! We’ll be releasing more in the future, so make sure to keep an eye out!

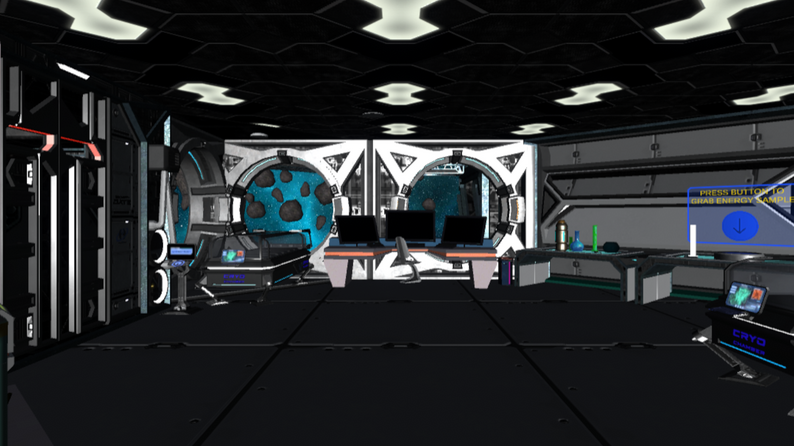

SELENA VR

You’re out of this world…literally! Your space shuttle has been through an asteroid storm and you are responsible for navigating through the aftermath. Through this experience, you will be challenged to regulate your emotions to remain calm and get through the obstacles with the help of SELENA.

Citations

The history of virtual reality (VR). SPREE Interactive. (2023, April 13). https://jointhespree.com/the-history-of-virtual-reality/

Lie, S. S., Røykenes, K., Sæheim, A., & Groven, K. S. (2023). Developing a virtual reality educational tool to stimulate emotions for learning: Focus Group Study. JMIR Formative Research, 7. https://doi.org/10.2196/41829

Walker, G., & Venker Weidenbenner, J. (2019). Social and emotional learning in the age of virtual play: Technology, empathy, and learning. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 12(2), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/jrit-03-2019-0046Zhang, F., Zhang, Y., Li, G., & Luo, H. (2023). Using virtual reality interventions to promote social and emotional learning for children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Children, 11(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010041